Aboriginal Artists – Australian Indigenous Artists

Indigenous Australian Aboriginal Art is the oldest ongoing form of artistic expression in the world. The earliest forms of Aboriginal art were rock carvings and paintings, body painting and ground designs. There are engravings on cave walls in Arnhem Land dating back at least 60,000 years. One of the largest collections of rock art is in the heritage listed Dampier Archipelago in Western Australia, where the rock engravings are thought to number in the millions.

Australian Aboriginal people have no written language of their own, and so the important stories central to the people’s culture are based on the traditional icons and information in the artwork, which go hand in hand with recounted stories, dance or song, helping to pass on vital information and preserve their culture. Aboriginal art on canvas and board only began 40 years ago. In 1971, Geoffrey Bardon a school teacher working with Aboriginal children in Papunya, noticed the Aboriginal men, while telling stories to others, were drawing symbols in the sand. He encouraged them to put these stories down on board and canvas, and there began the Aboriginal art movement.

A large proportion of contemporary Aboriginal art is based on important ancient stories and symbols centered on ‘the Dreamtime’ – the period in which Indigenous people believe the world was created. The Dreamtime stories are up to and possibly even exceeding 50,000 years old, and have been handed down through the generations. Paintings are also used for teaching: A painting (in effect a visual story) is often used by Aboriginal people for different purposes, and the interpretations of the iconography (symbols) in the artwork can vary according to the audience. So the story may take one form when told to children and a very different and higher level form when speaking to initiated elders.

Aboriginal art is regional in character and style, so different areas with different traditional languages approach art in special ways. Much of contemporary Aboriginal art can be readily recognised for the community where it was produced. Dot painting is specific to the Central and Western desert, cross-hatching and rarrk design and x-ray paintings come from Arnhem Land, Wandjina spirit beings come from the Kimberely coast. Preference for ochre paints is marked in Arnhem Land and east Kimberley. Other stylistic variations identify more closely to specific communities.

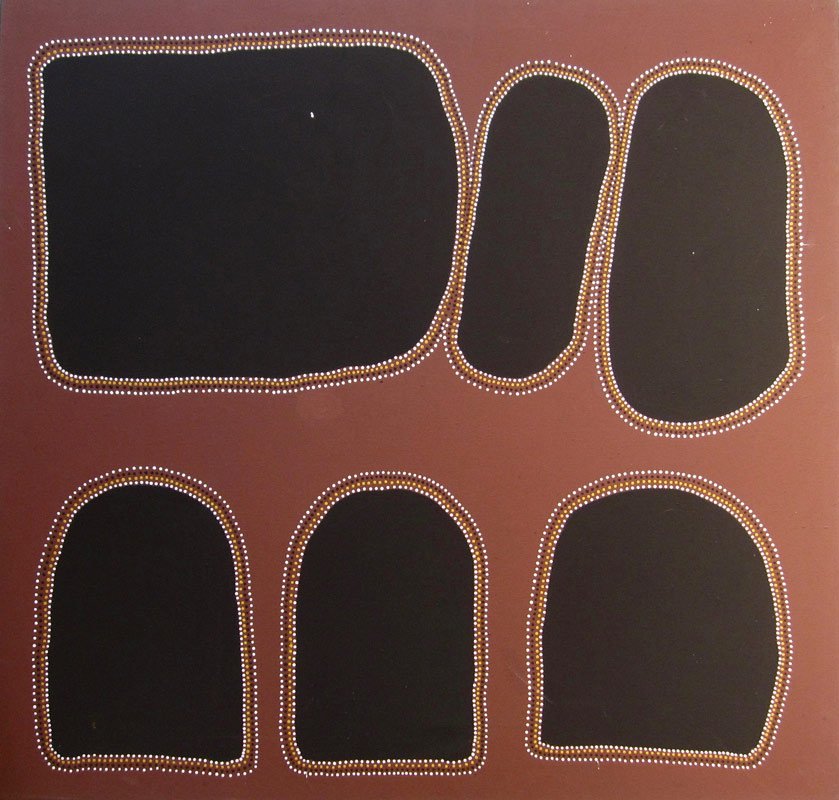

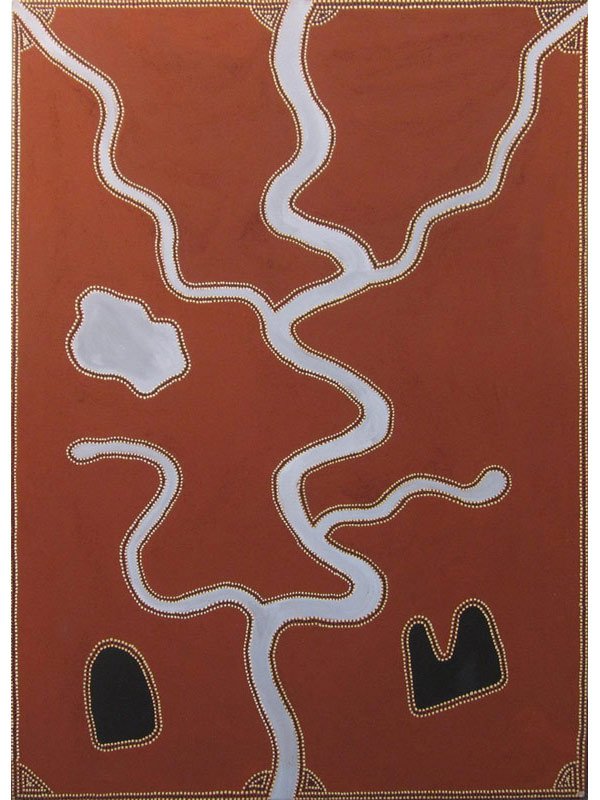

Wakartu Cory Surprise

Australian Indigenous Aboriginal Artist

Wakartu Cory Surprise was a highly regarded award-winning indigenous artist. Born in the Great Sandy Desert around 1929 she never knew her mother or father who died when she was a child. Painting in acrylics, Cory’s themes included Dreamtime stories, waterholes and rockholes and the country of her mother and brother (Mayita). Wakartu Cory Surprise died in 2011.

“I was born at Tapu in the Great Sandy desert around 1929. Tapu is my father’s country and Kurtal is my mother’s country. My parents died when I was a baby. I grew up at Wayampajarti and that is my country now. I don’t remember my mummy or daddy. They passed away in the desert. When I was crawling, my sister-in-law Trixie took me to Christmas Creek. I was promised to one old man who had two wives. We had no clothes when we went in. We were frightened of the Station Manager so we ran away from that place. Two times we ran away to the desert.

I walked out from the bush as a young woman with my two brothers. We were living at Wayampajarti and around that country there. At Wayampajarti there is a jila (permanent waterhole) where Kalpartu (an ancestral snake) lives. When we lived out in the bush we learnt the law. We learnt where the water is, where our country is and where to find food. You have to be careful not to go to the wrong places because you might make the Kalpurtu (spirit snake) angry or the other ones like Kukurr, Murungkurr, Parlangan. You could make other people angry too. You need permission to go to other people’s country.

I went to the desert with my husband to look for kumanjayi (deceased) Pijaju out there, then we all came back for ceremony. My husband did contract work building fences. I followed him on those contracts. I worked as a camp cook. I cooked food for big mobs of people. I cleaned, cooked and milked goats. We worked at Quanbun Downs, Jubilee Station, Yiyili and Cherrabun Station. Then I lived mainly at one place, GoGo Station (near Fitzroy Crossing) until I was old. I came to Fitzroy Crossing in the 1950s. I have a big mob of kids and some of them have passed away now. I first started painting at Karrayili Adult Education Centre in the early eighties. We told our stories through painting and learned to speak to kartiya (European person). I also did painting at Bayulu community near Fitzroy Crossing. That’s how I told my story to kartiya. We worked on paper then, not canvas or board.

When I paint, I think about my country, and where I have been travelling across that country. I paint from here (points to head – thinking about country) and here (points to breasts, collarbone and shoulder blades – which is a reference to body painting). I think about my people, the old people and what they told me and jumangkarni (Dreamtime). When I paint I am thinking about law from a long time ago. I like painting, it’s good. I get pamarr (word for rock, stone money) for it. I can buy my food, tyres and fi x my car. I give some money to my family and I keep some for myself. Nobody taught me how to paint, I put down my own ideas. I saw these places for myself, I went there with the old people. I paint jilji (sand hills), jumu (soak water), jila (permanent waterhole), jiwari (rock hole), pamarr (hills and rock country), I think about mangarri (vegetable food) and kuyu (game) from my country and when I was there.”

CV: Wakartu Cory Surprise

Date of Birth: 01/07/1929

Skin: Nyapana

Language: Walmajarri

Country: Pirrmal, Great Sandy Desert

Died: 2011

AWARDS:

- 2010 WA Indigenous Art Award

- 2009 Western Australian Premier’s Indigenous Art Award Winner of the ‘WA $10,000 Artist’ Award

- 2008 25th Telstra National Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art Award Highly commended

- 1997 14th Telstra National Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art Award Winner of the ‘Telstra Work on Paper’ Award

COLLECTIONS:

- National Museum of Australia, Canberra, ACT

- National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, ACT

- National Gallery of Victoria

- Art Gallery of New South Wales

- Charles Darwin University

- Steve Luzco Collection, San Franciso, USA

- Sammlung Alison and Peter W Klein Collection, Germany

- Laverty Collection

- HBL Collection, Melbourne

- Harriett and Richard England Collection

- Fitzroy Crossing High School

- Fitzroy Crossing Hospital

SOLO EXHIBITIONS:

- 2011 Wakartu Cory Surprise: A retrospective collection of paintings, Seva Frangos Art, Perth, WA

- 2007 Wakartu Cory Surprise, Silvershot Gallery Raft Artspace, Melbourne, VIC

- 2006 Wakartu Cory Surprise: New Works, Raft Artspace, Darwin

- 2006 Wakartu Cory Surprise, Silvershot Gallery Raft Artspace, Melbourne, VIC

- 2006 Mangkaja Arts Presents Wakartu Cory Surprise, Raft Artspace, Darwin, NT

- 2005 Cory and Friends, ReDot Gallery, Singapore

- 2004 Wakartu Cory Surprise, Boutwell Draper Gallery, Sydney

GROUP EXHIBITIONS:

- 2013-2014 My Country: Contemporary Art from Black Australia, Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, QLD and Auckland Art Gallery- Toio Tamaki, Auckland, NZ

- 2009 Mangkaja Artists 60×60 Randell Lane Fine Art, WA

- 2009 Sharing Difference on Common Ground Holmes a Court Gallery, Perth, WA and Kimberley Aboriginal Artists

- 2009 26th Telstra National Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art Award Museum and Art Gallery Northern Territory

- 2009 Wakartu Cory Surprise Alison Kelly Gallery, VIC

- 2009 Celebrating Country: Kinship and Culture Seymour College, Glen Osmond, SA

- 2009 Shalom Gamarada Caspary Conference Centre, University of NSW

- 2009 Western Australian Indigenous Art Award Art Gallery of Western Australia, Perth, WA

- 2009 Sitting Down with Jukuja & Wakartu RAFT Artspace, Darwin

- 2009 Senior Artists from Fitzroy Crossing Suzanne O’Connell Gallery, Brisbane, QLD

- 2009 Mangkaja Survey Show Short St Gallery, Broome

- 2008 The Other Thing: a survey show Charles Darwin University Art Collection, NT

- 2008 Wet n’ Wild Artkelch, Freiburg, Germany

- 2008 Mangkaja Arts A P Bond Art Dealer, Adelaide, SA

- 2008 Marnintu Maparnana ReDot Gallery, Singapore

- 2008 The Canning Stock Route Project Beijing International Olympic Committee Expo, China

- 2008 Shalom Gamarad Caspary Conference Centre, University of NSW

- 2008 Mangkaja Artists WA Randell Lane Fine Art, Perth

- 2008 25th Telstra National Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art Award Museum and Art Gallery Northern Territory

- 2008 Divas of the Desert Gallery Gondwana, Sydney

- 2008 Waterholes and Bush Tucker Bridget McDonnell Hampton Gallery, VIC

- 2008 Women On Country Suzanne O’Connell Gallery, Brisbane

- 2008 Bendi Lango The Indigenous Scholarship Fund, Sydney and Fireworks Gallery, Brisbane, QLD 2007 X Marks the Spot Wooloongabba Art Gallery, Brisbane

- 2007 Jila, Jilji and Miyi Cool Art Gallery, Coolum Beach, QLD

- 2007 Salt Water Fresh Water Central TAFE Art Gallery, Northbridge, WA

- 2007 Women Artists of Fitzroy Crossing Raft Artspace, Darwin,

- 2007 Mangkaja Arts – Fitzroy Crossing ARTKELCH, Germany

- 2007 24th Telstra National Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art Award Museum and Art Gallery Northern Territory

- 2007 Palya Art in Melbourne The Barn, Melbourne, VIC

- 2007 Bendi Lango The Indigenous Scholarship Fund, Sydney and Fireworks Gallery, Brisbane, QLD

- 2006 Mona Chugana & Cory Surprise Short St Gallery, Broome, WA

- 2006 Depth & Divergence Cullity Gallery, UWA, Perth, WA

- 2006 Mangkaja Group Show Boutwell Draper Gallery, Sydney, WA

- 2005 True Colours – Recent works from Queensland College of Art Gallery, Fitzroy Crossing Griffith University, QLD

- 2005 Surprise; Cory & Friends ReDot Gallery, Singapore

- 2005 Mangkaja Group Show Raft Artspace, Darwin, NT

- 2005 Colourfi elds Gallery Gondwana, Alice Springs NT

- 2005 Too Much Good Work Raft Artspace, Darwin, NT

- 2005 22nd Telstra National Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art Award Museum and Art Gallery Northern Territory

- 2004-2005 Colour Power: Aboriginal Art Post 1984 National Gallery of Victoria

- 2004 This is Still My Country: 10 Years On Perth International Arts Festival, Artplace, WA

- 2004 Ngurrara Canvas Perth Concert Hall, Perth International Arts Festival, WA

- 2004 Wakartu Cory Surprise & Widjee Henry Short Street Gallery, Broome, WA

- 2004 Over the Top Frementle Art Centre, Perth, WA

- 2003 Mangkaja Women Raft Artspace, Darwin, NT

- 2003 Jila, Jumu, Jiwari & Wirrkuja University of Western Australia, Cullity Gallery, Perth, WA

- 2003 Fitzroy Fusions Raft Artspace, Darwin, NT

- 2002 Group Show Flinders Lane Gallery, Melbourne, VIC

- 2002 Recent works from Mangkaja Arts Short St Gallery, Broome, WA

- 2002 Short on Size Short St Gallery, Broome, WA

- 2001 Ngurrara Canvas National Gallery of Australia, ACT

- 2001 Mangkaja Arts Ten Years On – Mangkaja’s 10 Year Anniversary Show Tandanya, Adelaide, SA 2001 Fitzroy Women Short St Gallery, Broome, WA

- 2001 Short on Size Short St Gallery, Broome, WA

- 2000 Noumea-Pacifififi que 2000 Biennale D’Art Contemporain de Noumea

- 2000 Short on Size Short St Gallery, Broome, WA

- 2000 Past modern, Australia Square Short St Gallery, Sydney, NSW

- 1999 Ngurrara Japingka Gallery, Fremantle, WA

- 1999 Short on Size Short St Gallery, Broome, WA

- 1998 Group Show Rebecca Hossack Gallery, London

- 1997 14th Telstra National Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art Award Museum and Art Gallery Northern Territory

- 1997 Group Show Hogarth Gallery, Sydney, NSW

- 1996 Group Show Hogarth Gallery, Sydney, NSW

- 1995 Group Show Australian Perspectives Gallery, Brisbane, QLD

- 1995 Kimberley Art Melbourne, VIC

- 1995 12th Telstra National Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art Award National Tour

- 1994 Ngajakura Ngurrara Minyarti: This is My Countrym Festival Of Perth Exhibition, Artplace, WA 1993 Images of Power National Gallery of Victoria

- 1993 Mangkaja Women Fremantle Arts Centre, Perth, WA

- 1992 Group Show Hogarth Gallery, Sydney, NSW

- 1991 Karrayili Tandanya, National Aboriginal Cultural Institute, Adelaide, SA

PUBLIC ART:

- 2009 Broome Prison – Panel design project

- 2008 Fitzroy Valley Education Centre – panel project

- 2008 Fitzroy Hospital – Wall design project, paintings on canvas, nurse base floor design

PUBLICATIONS:

- 2009 Kimberley Aboriginal Artists, Sharing Difference on Common Ground

- 2009 Collections australiennes contemporaines du musee des Confluences Aborigenes

- 2009 Deutscher and Hackett, 25 March, Important A Aboriginal Art

- 2009 Collaborations – Wakartu Cory Surprise and Ildiko Kovacs, Australian Aboriginal Art

- 2007 Art Gallery New South Wales, One Sun One Moon, Aboriginal Art in Australia

- 2006 Art Gallery of Western Australia, Western Desert Satellites: Works from the Western Australian State Art Collection

- 2004 National Gallery of Victoria, Colour Power: Aboriginal art post 1984

- 2003 Exhibition catalogue, Cullity Gallery UWA Perth / Mangkaja Arts Resource Agency, Martuwarra and Jila, Jumu, Jiwari and Wirrkuja

- 2003 New Yorker Magazine July 28, The Painted Desert the Fate of an Aboriginal Masterpiece

PUBLICATIONS/FILMS:

- 2002 Pat Lowe, Hunters and Trackers of the Australian Desert

- 2000 Oxford University Press and The Australian National University, Oxford Companion to Aboriginal Art and Culture / Ngurrara Entry

- 2000 National Aboriginal Cultural Institute – Tandanya, Painting Up Big, The Ngurrara Canvas

- 2001 Kent Town, S. Aust. Wakefi eld Press in association with the National Aboriginal Cultural Institute – Tandanya, Kaltja now: Indigenous Arts Australia

- 2000 IATSIS Canberra, Karrayili: The History of Karrayili Adult Education Centre 1998 Video Documentary / SBS Television, Jila Painted Waters of the Great Sandy Desert

- 1996 Karrayili Adult Education Centre and Mangkaja Arts exhibition catalogue, Minyarti Wangki NgaJukura Ngurrarajangka (This Is The Word From My Country)

- 1994 Exhibition Catalogue, Ngajakura Ngurrara Minyarti 1994 The Art Gallery of NSW, Yiribana: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Collection

- 1993 Exhibition catalogue, Fremantle Art Centre, Mangkaja Women

- 1993 National Gallery of Victoria, Images of Power: Aboriginal Art of the Kimberleys

- 1991 Exhibition catalogue, Tandanya Aboriginal Cultural Institute, Adelaide, Karrayili: Ten Years On

- 1991 Exhibition catalogue, Art Gallery Of New South Wales, Aboriginal women

JahRoc Galleries currently have no paintings by Wakartu Cory Surprise.

Visit Tunbridge Gallery for any works available

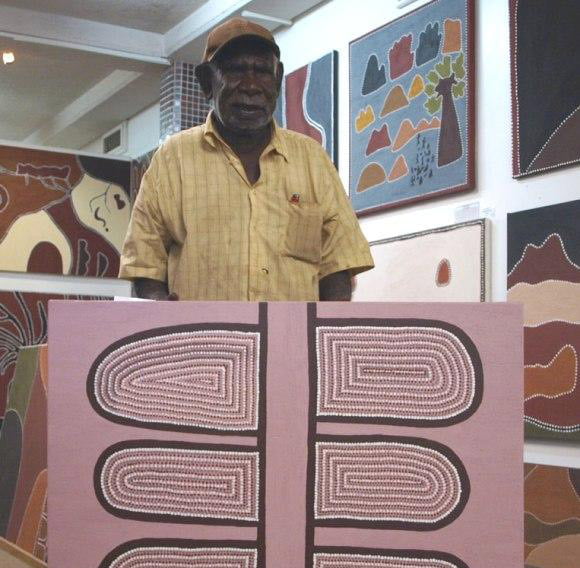

Billy Duncan

Australian Indigenous Aboriginal Artist

Billy Duncan’s art belongs to the iconic imagery of senior east Kimberley painters. His powerful, simplified forms are imbued with the energy of the sites of significance he paints.

Billy Duncan was born at Inverway Station in the Northern Territory in 1935. “Most of my life I have been droving cattle and working around the stations as a ringer and stockman. I used to come to Kununurra as a single bloke when I was younger, then I came here to live with my wife in the seventies.” After an accident during his stockman days, an injury to his knee forced Billy to change to working on farms in the Kununurra region. He has four children, two girls and two boys. Billy first started painting in the mid 1990’s.

CV: Billy Duncan

Date of Birth Circa 1934

Skin Jungari

Language Jaru

Country Moornboo

Dreaming Moornboo

Domicile Kununurra.

Medium

Natural Ochre and Pigment on Canvas

Themes

Traditional Country

Group Exhibitions

2016 ‘Family Connections”, Short St Gallery, Broome WA

2013 “Our Living Land” An Exhibition of Leading Artists from the East

Kimberley, Salvo Hotel, Shanghai, China

2013 “Our Living Land” An Exhibition of Leading Artists from the East Kimberley, OFOTO ANART Gallery, Shanghai, China

2012 “Sharing Difference on Common Ground” Geraldton Regional Gallery, Geraldton

2012 “Sharing Difference on Common Ground” Bunbury Regional Art Galleries, Bunbury

2012 “Sharing Difference on Common Ground” The Cannery Arts Centre, Esperence

2011 “Sharing Difference on Common Ground” Alcoa Mandurah Art Gallery, Mandurah

2010 “Sharing Difference on Common Ground” CCAE Darwin NT

2010 “Living Country” Tunbridge Gallery Margaret River WA

2009 “Danggang/Garardeng Red Ochre White Ochre” Mossensons Galleries Melbourne VIC

2009 “Miriwoong Country” Gecko Gallery Broome WA

2009 Celebrating Country: Kinship & Culture Seymour College Osmond SA

2009 “Sharing Difference on Common Ground” Holmes A Court Gallery

2009 “Best of the Best” Framed Gallery Darwin NT

2008 “Dawang – Our Country Our Place Our Home” Mossensons Gallery Melbourne VIC

2008 “Kimberley Ink and Ochre” Wollongong University NSW

2008 “Kimberley Ink” Northern Editions Darwin NT

2006 “Ochre Country” Gecko Gallery Broome WA

2004 “New works from New and Favourite Artists” Gadfly Gallery Perth

2003 “Art from the Heart” Thornquest Gallery Surfers Paradise QLD

Collections

National Gallery of Australia

Art Gallery of New South Wales

Clemenger Collection

Kerry Stokes Collection, WA

National Gallery of Victoria

Kluge Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection Virginia USA

Zhongfu Group Collection

JahRoc Galleries currently have no paintings by Aboriginal Artist Billy Duncan

Visit Tunbridge Gallery for any works available

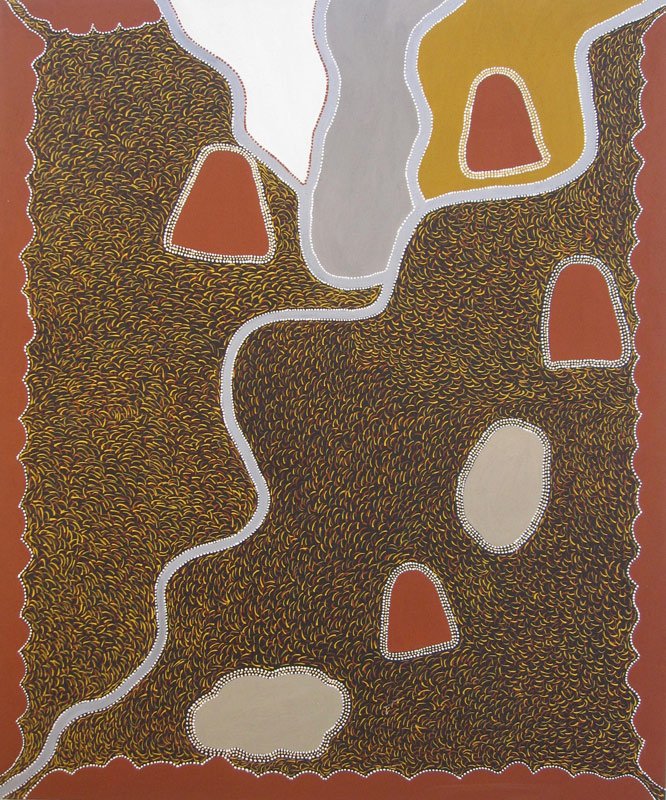

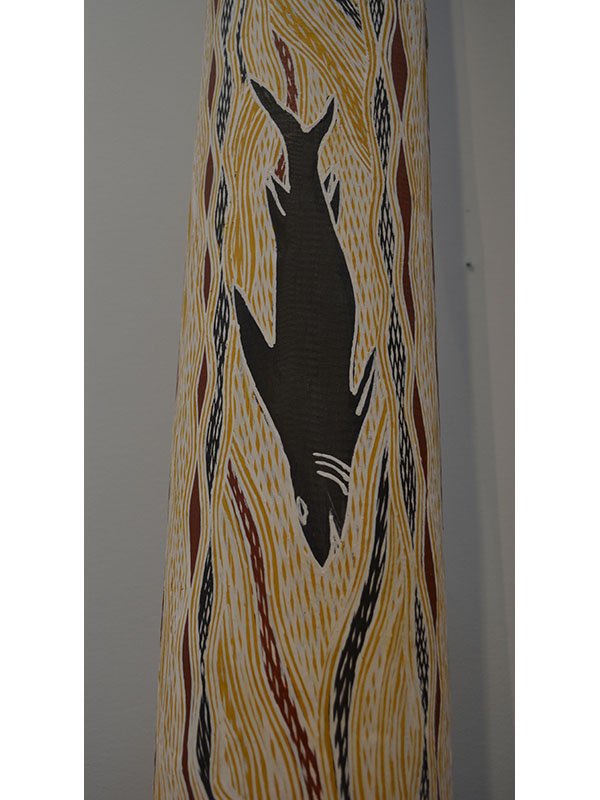

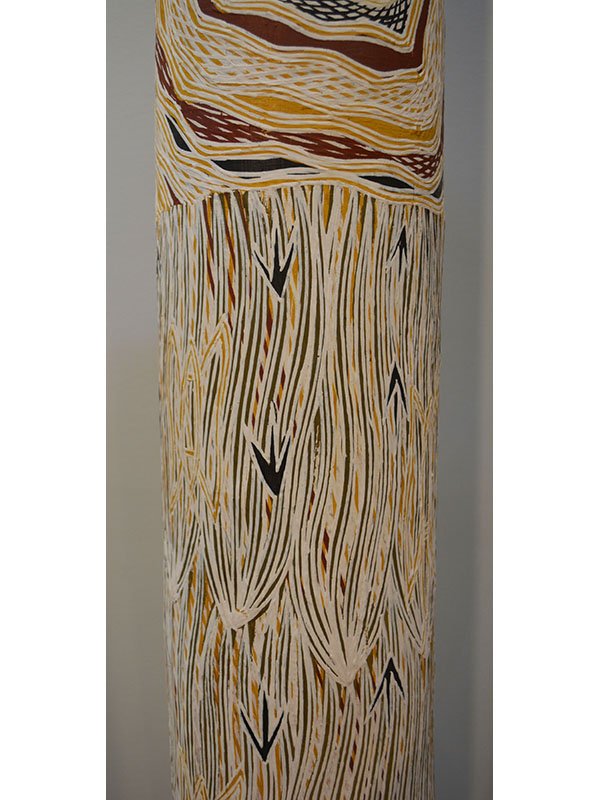

Peggy Griffiths

Australian Indigenous Aboriginal Artist

Born to Dianah Dingle and Frank Moore on Newry Station, Peggy’s father left the family during her early childhood years. The station manager’s wife advised her mother to send Peggy to school at the Kimberley Research Station. At 15 her mother took her out of school to Argyle Station and told she had been promised in marriage to Alan Griffiths when she turned 16. Peggy and her future husband were told to leave and they moved to Kununurra. Today they have 5 children and many grandchildren all of whom have been taught traditional stories and culture.

Peggy Griffiths is well informed about her family and bush life around the Goodim community and Newry. It was here that she saw old people taken away from the camp with chains around their necks and here that she learned to dance all the traditional dances.

Peggy Griffiths began working with Waringarri Aboriginal Arts in 1985, carving and painting boab nuts and boomerangs. She progressed to painting on canvas and working with limited edition prints (and was the first indigenous artist to win the prestigious Fremantle Print Award) and is committed to keeping the stories of her grandfather, Charlie Mailman, alive. Peggy Griffiths and her husband Alan Griffiths often paint side by side and are key performers and teachers of corroboree and traditional dances for their community. They have travelled widely, performing traditional dancers at arts festivals and events

Peggy Griffiths is now one of the most senior women artists at Waringarri Arts, teaching other artists and was until recently and for many years the Chairperson of Waringarri Aboriginal Arts, a community owned and led organization for its members. Her works document the traditional country of her father and grandfather and her most recent works capture the movement of wind through this spinifex country.

CV: Peggy Griffiths

Date of Birth c.1950

Skin Namij

Language Miriwoong

Country Newry Station, NT

Dreaming Morning Star

Domicile Kununurra, WA

Bush Name Marrdij Marrdijoroong

Mediums used:

Natural Ochre and Pigment on Canvas

Pigment on Paper

Limited Edition Prints

Carved Slate

Didjeridu’s

Themes

Traditional Country of her father and grandfather

Solo Exhibitions

2008 West meets East – Peggy Griffiths, Seva Frangos Art Perth WA

2005 Dreaming the Spinifex, Seva Frangos Art @ Span Galleries Melbourne

Group Exhibitions

2010 Sharing Difference on Common Ground, CCAE Darwin

2010 Sharing Difference on Common Ground, CCAE Darwin NT

2009 Sharing Difference on Common Ground, Holmes A Court Gallery Perth WA

2009 Best of the Best, Framed Gallery Darwin NT

2009 Alan & Peggy Griffiths, Short Street Gallery Broome WA 2008 Kimberley Ink and Ochre, Wollongong University NSW

2008 Kimberley Ink, Northern Editions Darwin NT

2008 Celebration Seva Frangos Art Perth WA

2005 When Waringarri Came to Town, Woolloongabba Art Gallery Brisbane QLD

2004 Waringarri 3 Women, Framed Gallery Darwin NT

2004 Kimberley Focus – Alan and Peggy Griffiths, Perth International Arts Festival Perth WA

2003 East Kimberley Art Short St Gallery Broome WA

2003 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Award Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory

2002 Kimberley Ochre, Red Rock Art at Cullen Bay NT 2002 Heyson Prize, Adelaide SA

2002 Love Your Work – 30 Year Exhibition, Fremantle Arts Centre Perth

2002 Warrgebarenkoo, Fremantle Arts Centre Perth WA

2001 Groundwork, Fremantle Arts Centre Perth WA

2000 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Award, Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory, Darwin NT

1999 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Award, Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory Darwin NT

1999 East Kimberley Art Award, Kununurra WA 1997 East Kimberley Art Award, Kununurra WA 1995 Fremantle Print Award, Perth WA

Collections

Fremantle Arts Collection, Perth, WA

Church Gallery Art Angels

Royal Perth Hospital Collection, Perth, WA

Kerry Stokes Collection, Perth, WA

Edith Cowan University, Perth, WA

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, ACT

Artbank Australia, Sydney, NSW

Art Gallery of Western Australia, Perth, WA

Parliament House Collection, Perth, WA

Parliament House Collection, Canberra, ACT

University of Technology Collection, Sydney, NSW

City of South Perth Collection, Perth, WA

Holmes A Court Collection, Perth, WA

Awards

1995 Fremantle Print Award, Fremantle, WA

JahRoc Galleries currently have no paintings by Aboriginal Artist Peggy Griffiths

Visit Tunbridge Gallery for any works available

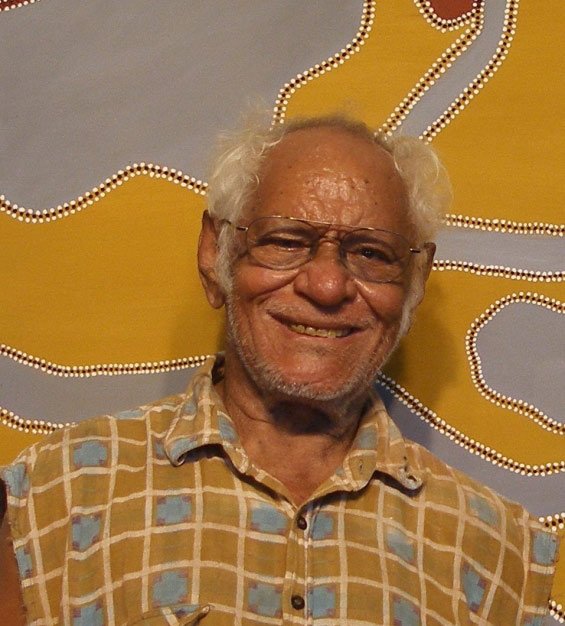

Alan Griffiths

Australian Indigenous Aboriginal Artist

Alan Griffiths was born at Victoria River Station, Northern Territory in 1933. He remained there until 1957 when he left to move to Katherine. Here he was head stockman on Beswick Station and then on Elsey Station near Mataranka, Northern Territory as well as Maninbelli Station, Elizabeth Downs, Delamere and Willaroo. Moving onto Wyndham, Western Australia, Alan Griffiths worked as a plumber before settling on Newry Station, again as a stockman as well as a cook. In 1965 he settled in Kununurra, living at Ivanhoe Station operating a tractor on a cotton farm. Alan Griffiths is married to his ‘promised bride’, Peggy Griffiths, and together they have five children, 27 grandchildren and many great grandchildren.

After his retirement from farm work in the early 1980s Alan Griffiths began painting his native country, mapping the significant features and cultural stories of the land. His repertoire of images includes paintings that map and name this country reflecting the artist’s intimate knowledge. His paintings also document traditional stories and corroborees, cattle mustering and camel treks. Today Alan’s ‘signature’ style involves depicted small figures performing corroborees, painted in a playful naive style.

Together with his wife Peggy Griffiths, he is dedicated to teaching traditional dances to his community and family. Alan is a respected law and culture man for both his traditional country near Timber Creek and for Miriwoong culture in Kununurra.

CV: Alan Griffiths

Date of Birth 1933

Skin Jangala

Language Ngarinyman / Ngaliwurru

Country Victoria River Downs, N.T.

Domicile Kununurra, WA

Solo Exhibitions

2006 “Alan Griffiths” CDU Gallery Charles Darwin University Darwin NT

2005 “Traditional Stories” Seva Frangos Art @ Span Galleries Melbourne VIC

2003 “Camel Trek Country” Span Galleries Melbourne VIC

Group Exhibitions

2016 “Family Connections”, Short St Gallery, Broome WA

2016 At Paris, Stephane Jacob and Suzanne O’Connell, Grand Palais, Paris, France

2016 “Birrgamibging Merndam – Things Made on Paper”, Tunbridge Gallery, Perth WA

2016 “Birrgamibging Merndam – Things Made on Paper”, Tunbridge Gallery, Perth WA

2015 Works of Significance, Tandanya Aboriginal Cultural Institute, TARNANTHI, Adelaide SA

2015 Salon15, Paul Johnstone Gallery, Darwin NT

2014 31st NATSIAA (National Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art Award) Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory Darwin NT

2014 In the Saddle, On the Wall, national touring exhibition, Kimberley Aboriginal Artists

2013 Traversing Borders: Art from the Kimberley, Queensland University of Technology Art Museum, Brisbane QLD

2013 Muswellbrook Art Prize, Muswellbrook Regional Art Centre

2013 “Our Living Land” An Exhibition of Leading Artists from the East Kimberley, Salvo Hotel, Shanghai, China

2013 “Ceremony” Hurstville Museum & Gallery, Hurstville NSW

2013 Waltzing Matilda Outback Art Show, Outback Regional Gallery, Winton QLD

2013 Waringarri Artists: Raison dêtre” Galerie Karin Carton, Versailles France

2013 “Our Living Land” An Exhibition of Leading Artists from the East Kimberley, OFOTO ANART Gallery, Shanghai, China

2013 30th NATSIAA (National Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art Award) Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory Darwin NT

2012 “Sculpture is Everything – Contemporary works from the collection” Gallery of Modern Art Brisbane QLD

2012 NATSIAA MAGNT Darwin NT

2012 “Sharing Difference on Common Ground” The Cannery Arts Centre, Esperence

2012 “Sharing Difference on Common Ground” Geraldton Regional Art Gallery, Geraldton

2012 “Sharing Difference on Common Ground” Bunbury Regional Art Galleries, Bunbury

2011 “Sharing Difference on Common Ground” Alcoa Mandurah Art Gallery, Mandurah

2010 “Northern Impressions” Northern Editions and Artback NT Touring Exhibition

2010 “Small Presents Big Presence – 8 Artists 100 Artworks” Seva Frangos Art Perth WA

2010 “Sharing Difference on Common Ground” CCAE Darwin NT

2009 “Best of the Best” Framed Gallery Darwin NT

2009 “Alan & Peggy Griffiths” Short Street Gallery Broome WA

2009 “Sharing Difference on Common Ground” Holmes A Court Gallery Perth WA

2008 “Kimberley Ink and Ochre” Wollongong University NSW

2006 “Celebration” Seva Frangos Art Perth WA

2005 “When Waringarri Came to Town” Woolloongabba Art Gallery Brisbane QLD

2005 “Indigenous Art” Australian Embassy Paris France

2005 “Kimberley Ink” Northern Editions Darwin NT

2004 Kimberley Focus Concert Hall Perth International Arts Festival

2004 Hunter Art 1 Newcastle Regional Gallery Newcastle NSW

2004 Waringarri Song and Dance Cycle Sunken Gardens UWA Perth

2003 “Moon Show” Arthouse Gallery Rushcutters Bay Sydney NSW

2003 “Kimberley Art” Short Street Gallery Broome WA

2002 Heyson Prize Adelaide SA

2002 Kimberely Ochre Cullen Bay Darwin NT

2002 “Warrgebarenkoo” Fremantle Arts Centre Perth WA

2001 “Groundwork” Fremantle Arts Centre Perth Wa

2001 “All About Art” Alcaston Gallery Melbourne VIC

2001 “New Wave Kimberley Art” Seva Frangos Art Margaret River WA

2000 “National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Award” Museum and Art Gallery of Northern Territory Darwin NT

1999 “Kimberley Art Award” Kununurra WA

1999 “National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Award” Museum and Gallery of Northern Territory Darwin NT

1997 “National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Award” Museum and Gallery of Northern Territory Darwin NT

1995 Fremantle Print Award Perth WA

Collections

Art Equity Collection

Art Gallery Of Queensland

Artbank Australia Sydney

Bachelor Institute Of Advanced Education Darwin NT

Broadmeadows Health Service Collection, Melbourne

Cable Beach Resort, Broome (Commission)

City Of Perth Collection

Edith Cowan University Collection, Perth

Kluge Ruhe Aboriginalart Collection Virginia Usa

Musee De Confluence Lyons France

National Gallery Of Australia Collection

Parliament House Collection Canberra

Royal Perth Hospital Collection

University Of Wollongong Collection Nsw

Water Corporation Wa Collection

Zhongfu Group Collection

Art Gallery Of Western Australia

National Gallery Of Australia Canberra

Department Of Housing, Government Of Western Australia

Ronald Mcdonald House

Wesfarmers Collection Of Australian Art, Perth

Awards

2015 Living Treasure, Department of Culture and the Arts, WA

Publications

2009 Sharing Difference on Common Ground, Touring Exhibition Catalogue

2013 Our Living Land, Exhibition Catalogue

2010 Alan Griffiths, Documentary Alex Smee

2006 Arts Backbone, Vol. 6, March 2006.

2004 Perth International Arts Festival Catalogue, February, 2004.

2002 Berndt Museum Newsletter, September, 2002.

JahRoc Galleries currently have no paintings by Aboriginal Artist Alan Griffiths

Visit Tunbridge Gallery for any works available

Djambawa Marawili AM

Australian Indigenous Aboriginal Artist

Djambawa Marawili is first and foremost a leader, and his art is one of the tools he uses to lead. His principal roles are as a leader of the Madarrpa clan, a caretaker for the spiritual well-being of his own and other related clan’s and an activist and administrator in the interface between non-Aboriginal people and the Yolnu (Aboriginal) people of North East Arnhem Land.

Djambawa Marawili is an artist who has experienced mainstream success (as the winner of the 1996 Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Award – Best Bark Painting Prize) and as an artist represented in most major Australian institutional collections and several important overseas public and private collections, but for whom the production of art is a small part of a much bigger picture.

As well as being the Chairman of ANKAAA’s Board of Directors (2000 – 2014), Djambawa Marawili AM (b.1953) has held numerous other positions, including Chairperson of Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Centre (1994 – 2000), Chairperson of Laynhapuy Homelands Committee (1995 – 1997), Board Member of the Australia Council, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Arts Board (2004 – 2009) and Board Member of the Northern Land Council. In 2014 Djambawa was appointed to the Prime Minister’s Indigenous Advisory Council.

In 2015 Djambawa Marawili continued to chair ANKAAA whilst also serving as deputy Chairman of Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Centre and sitting on the board of Laynhapuy Homelands and the Northern Land Council. As ceremonial leader of the Madarrpa clan of North East Arnhem Land, Djambawa uses his art to communicate his wider socio-political aims, drawing on the strong foundations of Yolngu culture to educate, inspire and seek justice for his people.

Through various advocacy, administrative and educative roles, Djambawa acts as an interface between Yolngu and the wider non-Indigenous population of Australia. He was a participant in the production of the Barunga Statement (1988), which led to Bob Hawke’s promise of a treaty between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people, the Royal Commission into Black Deaths in Custody (established in 1989) and the formation of ATSIC in 1990.

As he has consistently throughout his life, Djambawa uses painting to show the sacred designs that embody his right to speak as a part of the land, whether it be above ground or under the sea. He was instrumental in the initiation of the Saltwater: Yirrkala Bark Paintings of Sea Country exhibition, which toured nationally from 1999 – 2001. He co-ordinated the 2004 Sea Rights claim in the Federal Court which eventuated in the High Court’s determination that Yolngu did indeed own the land between high and low water mark (2008 Blue Mud Bay case).

Djambawa’s work is held in many important public and private collections including Art Gallery and Museum, Glasgow, Scotland; Art Gallery of Western Australia, Perth; JW Kluge Collection, Virginia, USA; National Gallery of Australia, Canberra; National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne; President of India Art Collection; National Maritime Museum, Sydney; Northern Territory Supreme Court, Darwin; Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney; Holmes a Court Collection and Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane.

CV: Djambawa Marawili AM

Date of Birth 1953

Clan Yithuwa Madarrpa

Languages Yolngu Matha, Dhuwala, Dhuwaya, Dbjambarrpuy, Kriol Gumatj, Anindilyakwa, English

Moiety Dhuwa

Homeland Arnhem Land, Baniyala / Yilpara

Awards

- 1996 Best Bark Painting – 13th National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards

- 2004-5 Australia Council Fellowship

- 2008 Major protagonist of the successful Blue Mud Bay case in the High Court

- 2009 Co-Judge of the 27th National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Award

- 2010 Membership (an AM) in the General division of the Order of Australia

- 2011 Highly Commended Telstra NATSIAA, MAGNT Darwin, NT

Collections

- Nga Art Bank Sydney Art Gallery and Museum

- Kelvingrove, Glasgow Scotland

- Art Gallery of Western Australia

- Australian Capital Equity the Kerry Stokes Collection

- JW Kluge Collection

- Virginia USA National Gallery of Australia

- Canberra. National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

- Queensland University of Technology Art Collection Crafts Museum

- New Delhi, India. A collaborative canvas 16’ x 4’ with artists Liawaday Marawili (wife) and Indian ‘tribal’ artists Jangarh Singh Shyam and Bhuri Bai President of India Art Collection, a collaborative work with JS Shyam and B Bai, presented to the President by the Australia India Council in New Dhelhi 1999

- Australian Capital Equity Art Collection, Perth, WA

- Saltwater – Yirrkala Bark Paintings of Sea Country

- National Maritime Museum, Darling Harbour Sydney

- NSW Sydney Opera House

- NSW Kerry Stokes Collection

- NT Supreme Court

- LeviKaplan Collection Art Gallery NSW British Open

- University Art Museum Milton Keynes England Holmes a Court Collection Woodside Energy Ltd.

- Collection Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, Queensland

Exhibitions

- 1984 Aboriginal Art, an Exhibition presented by the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, Canberra.1984, Baniyala Artworks, Collectors Gallery, Sydney

- 1984, Baniyala Artworks, Crafts Council Gallery, Sydney

- 1986 Painted objects from Arnhem Land, University Drill Hall Gallery (Pod), Canberra, ACT

- 1989 Aboriginal Art, The Continuing Tradition, National Gallery of Australia

- 1990 Keepers of the Secrets, Aboriginal Art From Arnhem Land, Art Gallery of WA, Perth, WA.

- 1994 11th National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards Exhibition, Museum and art Gallery of the Northern Territory, Darwin NT

- 1995 Miny’tji Buku-Larrnggay, Paintings from the East, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne Vic.

- 1995 12th National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards Exhibition, Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory, Darwin NT

- 1996 Miny’tji Dhawu, Savode Gallery Brisbane

- 1996, 13th National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards Exhibition, Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory, Darwin NT. (Winner best Bark painting Category)

- 1996 Big Bark, Annandale Gallery, Sydney.

- 1997 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards Exhibition, Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory, Darwin NT

- 1997 Native Title, Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney NSW

- 1997 Djambawa, William Mora Gallery, Melbourne Vic.

- 1998 Hollow Logs from Yirrkala, Annandale Gallery, Sydney.

- 1998 The Fifteenth National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards, Museum and Art Galleries of the NT, Darwin

- 1999 Carvings by Djambawa Marawili, Alcaston House Gallery, Melbourne, Vic.

- 1999-2001 Saltwater Country – Bark Paintings from Yirrkala, A National Tour – The Drill Hall Gallery, ANU, Canberra – John Curtin Gallery, Curtin University, Perth WA – National Australian Maritime Museum, Darling Harbour, Sydney NSW – Museum of Modern Art at Heide, Melbourne Vic – Araluen Art Centre, Alice Springs NT. Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane Qld

- 1999 16th National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards, Museums and Art Galleries of the NT, Darwin NT.

- 1999 Gapu Minytji, an exhibition of sacred water designs of the Australian Aboriginals of north east Arnhem Land – Crafts Museum – New Delhi India.

- 2000 Fifth National Cultural Heritage Art Awards, Old Parliament House, Canberra, ACT

- 2000 Art Fair 2000, with Alcaston House Gallery, Melbourne Vic

- 2000 Annandale Galleries, Sydney, NSW: group show with Galuma and Dhukal Wirrpanda

- 2001 Ben Grady Gallery, Yolngu Bark

- 2001 18th NATSIAA, MAGNT

- 2002 Garma Larrakitj Installation

- 2002 Sydney Opera House Larrakitj installation

- 2003 Buwayak, Annandale Galleries Sydney

- 2003 Wukidi installation 29th June 2003 NT Supreme Court

- 2003 Abstractions , Drill Hall Gallery Canberra

- 2004 21st NATSIAA MAGNT

- 2004 Binocular: Looking closely at country, Ivan Dougherty Gallery UNSW COFA

- 2005 Kaplan Collection exhibition, Seattle Museum

- 2005 Source of Fire, Annandale Galleries Sydney-solo

- 2005 Gapan Gallery, Print Exhibition, Garma Festival.

- 2005 Yåkumirri, Raft Artspace (exhibition purchased by the Holmes a Court collection)

- 2005 Yåkumirri, Holmes a Court Gallery , Perth

- 2006 Walking together to aid Aboriginal Health, Shalom College UNSW

- 2006 Solo exhibition in Sydney Bienalle

- 2006 Gapan Gallery. Print Exhibition. Garma Festival

- 2006 Galuku Gallery, Print Exhibition,. Darwin Festival

- 2006 Asia Pacific Triennale Queensland Gallery of Modern Art opening Brisbane

- 2006 Bulayi Small Gems, Suzanne O’Connell Indigenous Art Brisbane

- 2007 Bukulungthunmi – Coming Together, One Place, Raft Artspace, Darwin, NT.

- 2008 Some Men I Have Met, Steve Fox of Mogo Raw Art, Mogo, NSW

- 2008 Berndt Etching Exhibition, Gapan Gallery, GarmaFestival.

- 2008 Berndt Etching Exhibition, Galuku Gallery, Darwin Festival

- 2008 “Bitpit” Yirrkala Sculpture, RAFT Artspace Darwin

- 2008 Outside Inside – bark and hollow logs from Yirrkala, Bett Gallery Hobart, Tas

- 2008 Melbourne Art Fair, Larrakitj, represented by Vivien Anderson Gallery, Melbourne, Vic

- 2008 25th National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards, Museum and Art Gallery of the NT, Darwin NT

- 2008 Etched in the Sun: Prints made by Indigenous artists in collaboration with Basil Hall & Printers 1997-2007, ANU, Canberra

- 2008 Ochre, Menzies Auction, Melbourne

- 2008 A Few Real Gems I Have Come Across, Mogo Raw Art and Blues, Mogo, NSW

- 2009 Larrakitj – the Kerry Stokes Collection, Art Gallery of Western Australia, Perth, WA

- 2009 After Berndt – Indigenart, Mossenson Gallery, Perth, WA

- 2009 3rd Moscow Biennale, ‘the Garage’, Moscow, Russia.

- 2009 Menagerie; Contemporary Indigenous Sculpture, Australian Museum and touring.

- 2010 17th Biennale of Sydney – ‘Larrakitj – the Kerry Stokes Collection, Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, NSW

- 2010 Djalkiri; We are standing on their names, Nomad Art, 24-Hour Art, Darwin Festival.

- 2011 Djambawa Marawili, Liywaday Wirrpanda and Nawurapu Wunungmurra, Annandale Galleries

- 2011 Telstra NATSIAA, MAGNT Darwin NT

- 2012 Seattle Art Museum Modern icons

- 2012 Barrku! RobyKing Gallery, Seattle in association with Harvey Art Projects

- 2012 Chiarascuro Gallery Santa Fe

- 2013 Djambawa,Vivien Anderson Gallery

- 2013 Prized Nomad Art Darwin

- 2014 The world is not a foreign land- new perspectives on contemporary Indigenous art; Timothy Cook, Djambawa Marawili, Ngarra, Rusty peters, Freda Warlapinni and Nyapanyapa Yunupingu , Ian Potter Museum of Art curated by Quentin Sprague.

- 2015 Lumggurma/North, Brumby Ute, USA

- 2015 Tuslusu Saltwater Istanbul Modern Istanbul Bienal Turkey

JahRoc Galleries currently have no artworks by Aboriginal Artist Djambawa Marawili AM

Visit Tunbridge Gallery for any works available

Galuma Maymura

Australian Indigenous Aboriginal Artist

Galuma Maymura is the surviving daughter of the great Narritjin. Gamula was one of the first Yolnu women to be instructed to paint (by her father) the sacred clan designs that were previously the domain of high ranking men. In preparation for her solo exhibition of her art she prepared the following statement:

“This is what I really learnt from my father. First when I was still in school at Yirrkala he used to let me sit next to him, me and my brothers and he used to show us all the paintings from Wayawu and Djarrakpi. And he’d say this is our paintings and I’m telling you this about the paintings for in the future when I’m passed away you can use them.

Then I forgot all about this when I was in school- then I stopped but I was still thinking the way he was teaching us. Then one day I decided to start on a bark by helping him at Yirrkala. Every afternoon after work I used to sit with him and paint little barks – mostly from Djarrakpi but a little from the freshwater country at Wayawu but not Milnaywuy.

Then I was keep on doing it over and over on cardboard until my hand it gets better and better and I put it in my mind, then it was working and I kept on doing it.

I went to Djarrakpi with my family to live with my father and my mother and brothers. My brothers passed away and we had to go back to Yirrkala. I left my father and mother there when I went to live at Baniyala. My husbands family were living there. I was teaching at the Baniyala school still doing a little bit of painting but mainly schooling. When father and family died I stopped painting – just doing school work.

Once I moved to Dhuruputjpi in 1982 I started to paint again because no one else was doing it and I was thinking about the way my father was talking and how did he handle all this. How did my father do all this- travel and paint- how to handle painting so I kept on thinking. I’m not really prouding myself but I wanted to do this painting as my father did it and to keep it in my mind. But I really want this painting to keep going. My gurrun he is looking after it as his Mari (mothers mothers side) and others are looking after it. I have to teach my kids incase someone might steal the designs. So my kids can know what their mothers paintings is”

As a participant in the groundbreaking exhibition ‘Buwayak’ at Annandale Galleries in 2003 and a winner of that year’s Best Bark painting prize at the Telstra Aboriginal Art Awards her significance cannot be overstated. Galuma Maymura’s health problems have not stopped her from painting or living in remote homelands of Dhuruputjpi, Djarrakpi or Yilpara. She is a fierce advocate and mainstay of homeland life.

CV: Galuma Maymura

Date of Birth 1951

Language Manggalili

Country Yirrkala, North-east Arnhem Land

Alternate Names Maymura, Maymaru, Maymurru, Wirrpanda

SOLO EXHIBITIONS

2014 The Torrent Galuma Maymuri, Annandale Galleries, Sydney, NSW

2007 Annandale Galleries, Sydney, NSW

2005 Solo exhibition in conjunction with Source of Fire

2001 Sacred Bark Paintings from Outstation artist Galuma Maymuru, Helen Maxwell Gallery, Canberra, ACT

1999 In Memory of Narritjin, William Mora Gallery, Melbourne, VIC

GROUP EXHIBITIONS

2016 Gapan 16 – Prints from Garma 2016 – Chapman & Bailey and Hanging Vallery, Melbourne VIC

2016 Tradition & Innovation – Paris Parcours des Mondes 2016-Aboriginal Signature • Estrangin Gallery

2015 Lundumirringu – Annandale Galleries, Sydney NSW

2015 Revolution: New work celebrating 20 years of printmaking at Yirrkala Print Space. – Nomad Art, Darwin 2015

2015 Buku-Larrnggay Mulka – Yirrkala Print Space Exhibition – Gapan Gallery, Garma Festival, Gulkula, Northeast Arnhem Land NT

2015 Mother to Daughter: On Art and Caring for Homelands – The Cross Art Projects, Sydney NSW

2013 30th Telstra National Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art Award – Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory, Darwin NT

2013 FOUND – Annandale Galleries, Sydney NSW

2013 Prized – Nomad Art, Darwin, NT

2012 The Philosophy of Water, Short St Gallery, Broome, WA

2010 17th Biennale of Sydney, ‘Larrakitj- the Kerry Stokes Collection’, Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney. NSW

2009 Larrakitj from Yirrkala, Indigenart- Mossenson Gallery, Perth WA

2009 Larrakitj – the Kerry Stokes Collection, Art Gallery of Western Australia,

2008 Outside Inside, Bett Gallery, Hobart, TAS

2007 Bukulunthnmi- Coming Together, One Place, Raft Artspace, Darwin,

2007 Galuku Gallery, Festival of Darwin, NT

2006 Dreaming their way- Australian Aboriginal Women Painters’, National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, USA

2006 Bulayi- Small Gems’, Suzanne O’Connell Gallery, Brisbane QLD

2005 Yakumirri, Holmes a Court Gallery, Perth, WA

2005 Yakumirri, Raft Art Space, NT

2004 Circle, Line, Column, Annandale Galleries, Sydney

2004 21st National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Award, Museum and Art Gallery of Northern Territory

2003 20th National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Award, Museum and Art Gallery of Northern Territory

2003 Larrakitj, Rebecca Hossack Gallery

2003 Buwayak, Annandale Galleries, Sydney, NSW

2002 Sydney Opera House Larrakitj Installation

2002 19th National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Award, Museum and Art Gallery of Northern Territory

2002 Bark Paintings by Galuma and Dhukal, Framed Gallery, Darwin, NT

2001 Garma Larrkitji Installation

2001 New from Old, Annandale Galleries, Sydney, NSW

2000 Fifth National Indigenous Heritage Art Awards, Old Parliament House, Canberra, ACT

1999/2001 Saltwater Country- Bark Paintings from Yirrkala, The Drill Hall Gallery, ANU, Canberra, ACT and touring

1998 15th National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Award, Museum and Art Gallery of Northern Territory

1997 14th National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Award, Museum and Art Gallery of Northern Territory

1996 Big Barks, Annandale Galleries, Sydney, NSW

1996 13th National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Award, Museum and Art Gallery of Northern Territory

1996 Miny’tji Dhawu, Savode Gallery, Brisbane, QLD

1992 9th National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Award, Museum and Art Gallery of Northern Territory

1984 The First National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Award, Museum and Art Gallery of Northern Territory

COLLECTIONS

Berndt Museum of Anthropology, University of Western Australia, Perth

National Museum of Australia, Canberra

The Kelton Foundation, Santa Monica, USA

JW Kluge Collection, Virginia, USA

The Gantner Myer Collection, Melbourne VIC

National Maritime Museum, Darling Harbour, Sydney, NSW

Sydney Opera House, Sydney, NSW

Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory

Kerry Stokes Iarrakitj Collection

Harland Collection

Ballarat Fine Art Gallery

Holmes a Court Collection

Seattle Art Museum

Woodside Energy Ltd. Art Collection

Liz and Colin Laverty Collection

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Gong Wapitja- Women and Art from Yirrkala, Gillian Hutchenson, Aboriginal Studies Press

Films from the Ian Dunlop series “the Yirrkala Project”; “Baniyala” and “One Mans Response”

Salt Water- Yirrkala Bark Paintings of the Sea Country. Buku-Larrngay Mulka Centre in conjunction with Jennifer Isaacs Publishing,1999

Art From the Land. University of Virginia, edited by Howard Morphy and Margo Smith Bowles 1999.

Spirit Country- Contemporary Australian Aboriginal Art by Jennifer Isaacs 1999

JahRoc Galleries currently have no paintings by Aboriginal Artist Galuma Maymura

Visit Tunbridge Gallery for any other works available